I am hugely optimistic about the role cryptocurrencies (such as bitcoin) will play in the future – and one of the reasons is that they enable us to build decentralised digital asset registers. I’ve written about this concept here.

In this post, I’ll explore some of the current thinking on how to build such a system.

The simplest way to think about this subject is to imagine you own one hundred twitter shares that you would like to sell and, because you’re one of these early-adopting trailblazers, you want to sell the shares for Bitcoins and want to do so using only the bitcoin system. Here’s how it could work:

As I write, Twitter shares trade for just over $40, so your one hundred shares would be worth about $4000. So you could announce to the world that a particular Bitcoin you own (strictly, a transaction output) is for sale and that you will give whoever buys it all the rights associated with the twitter shares… e.g. dividends, votes, etc. You don’t plan to transfer the share through the regular equity settlement systems in your country, though; you’ll remain the registered owner there… but provided you are trustworthy, the recipient will trust you to pass on the benefits you receive to them.

A Bitcoin today trades for about $300. So if you could find somebody who trusts you, they might be willing to pay you about $4300 for your special bitcoin ($300 for the Bitcoin plus $4000 for the rights to the shares). Perhaps they’d demand a discount to account for the ongoing counterparty risk they have to you. So let’s imagine they offer to pay you $4000 to keep the maths simple.

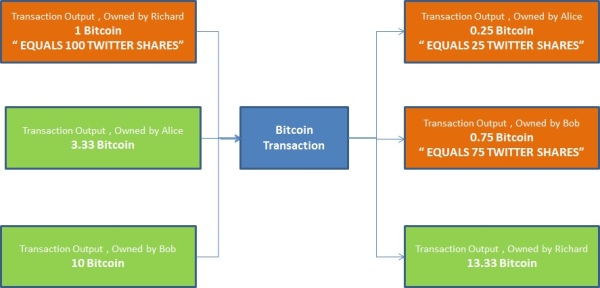

To make it interesting, let’s imagine that Alice is willing to buy 25% of your holding ($1000, or 3.33 XBT) and Bob wants 75% ($3000 or 10 XBT). What we want is for them to transfer these coins to you and for you to transfer your “special” (or, colored) coin to them so that, once you’re done, you have 13.33 XBT and they have a share of the colored coin.

Graphically, this is what it might look like:

In this picture, we see that a Bitcoin transaction has been constructed that has the following interesting properties (in reality, it may be done as a sequence of transactions and I’m not 100% sure you could actually do it this way for real on the current Bitcoin network but the concepts remain the same so we’ll stick with this for the purposes of this post)

- Alice and Bob pay their agreed amounts of Bitcoins into the transaction (i.e. their 25% and 75% share of the costs) – colored green in the diagram

- I pay in the coin I have previously asserted to be “equivalent” to 100 twitter shares – colored orange in the diagram

- Alice and Bob receive 25% and 75%, respectively, of the special (colored) coin so that everybody can now see that they are the owner of the coin, and hence entitled to their shares of any benefits associated with the shares – shown in orange on the right-hand side

- I receive Alice and Bob’s payments – shown in green on the right.

Easy, right? Well…. not quite.

The problem is step 3. If you are an independent third party arbitrating a future dispute, how do you know that the 0.25 XBT and 0.75 XBT received by Alice and Bob relate to the ‘colored’ 1XBT I paid in? What would have happened if I had also paid somebody else 0.75 XBT in that transaction? How would we know one of these payments was the special colored coin and one was just a regular bitcoin?

Worse, what would happen if Alice or Bob somehow temporarily forgot their coins were special and spent them as if they were normal coins? They could lose a fortune! It would be helpful if their wallet software warned them. Which means the wallet would need to be able to tell automatically. Worse, what if Bob used his colored coin as part-payment for a larger expense, with regular coins making up the difference? How on earth would the recipient interpret their receipt of a transaction output that was formed from combining colored and non-colored coins?!

The answer is that there is nothing in the core bitcoin system that allows you to tell. So various conventions have been proposed. The simplest is one that just relies on ordering, but there are others, none of them particularly satisfactory. But it’s being worked on. I think one piece of work in particular has helped in this space by generalising this problem by introducing the idea of a “color kernel“, whose job it is to decide which outputs are related to which types of coin. Projects such as bitcoinx are working on implementing a system based on these concepts.

In a future post, I’ll discuss a very different model, that of mastercoin.