I explained here how money moves around the banking system and how the Bitcoin system causes us to revisit our assumptions about what a payment system must look like. In this post, I turn my attention to securities settlement: if I sell some shares to you, how do they actually move from my account to yours? What is actually “moving”? What do I mean by “account”? Who is involved? What are the moving parts?

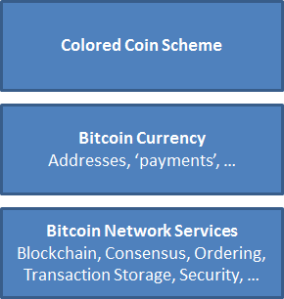

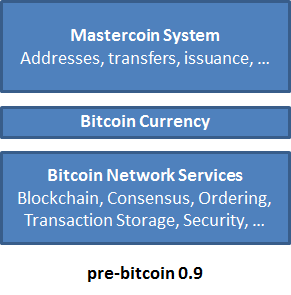

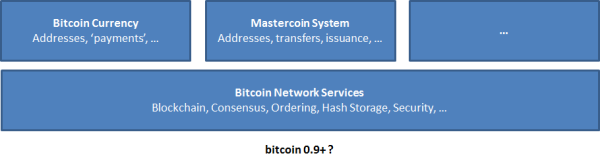

I have argued for some time that the Bitcoin system is best regarded as a global, decentralized asset register and that some of the assets it could register, track and transfer could be securities (stocks and bonds). In this post, I go back to basics to explain what actually happens behind the scenes today and use that to think through the implications should schemes such as ColoredCoins.org or MasterCoin gain traction. I’ve discussed these systems in a couple of articles here (coloured coins) and here (MasterCoin).

As in the previous article, my focus is on imparting understanding by telling a story and building up a narrative. This means some of the precise details may be simplified. So please don’t build a securities settlement system for your client using this article as your guide!

First, let’s establish some common ground.

Here are the simplifying assumptions I’m going to make:

- I’m going to invent a fictional company called MegaCorp

- I’m going to assume we start back in the days when certificates were in paper form. I’ll move to electronic systems later in the article but I think it helps first to think about paper – it helps us keep track of what’s really going on

- I’m going to rewrite history to suit the story. If you’re a historian of finance, this article is not for you!

- Finally, I’m going to assume that MegaCorp already exists, has issued shares and that they are in the hands of a large number of individuals, banks and other firms. I’m going to assume you’re one of these owners. How these shares were issued would be a fascinating story itself but there isn’t space here to talk about corporate finance, IPOs and all the rest. Google it: “primary market” activity is a really interesting area of investment banking.

So let’s get started. You own some MegaCorp shares and you want to sell them.

Selling shares if everything was paper-based

So… you own some shares in MegaCorp and you have a piece of paper that proves it: a share certificate. You’d like to sell those shares. Now you have a problem. How do you find somebody who is willing to buy them from you?

I guess you could put an advert in the paper or maybe walk around town wearing a sandwich board proclaiming your desire to sell. But it’s not ideal.

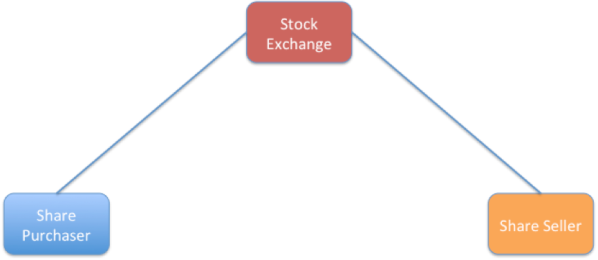

Figure 1 The fundamental problem: how does a seller find a buyer or a buyer find a seller?

The obvious answer is that it would all be so much easier if there were a place – a venue where people commonly in the business of buying and selling shares could get together and find each other. Happily, there are and we call such places stock exchanges. In the early days, they were simply coffee houses or under a Buttonwood tree in trading centres such as London. Over time, they became formalized. But the idea is the same: concentrate buyers and sellers in one place to maximize the chance of matching them with each other.

This adds a new box to our diagram: the stock exchange.

Figure 2 A stock exchange brings buyers and sellers together to help them execute trades

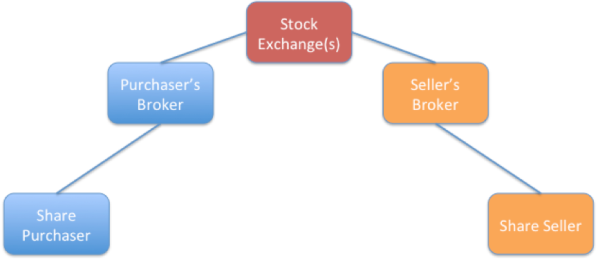

There are still some problems, however. What if you’re just an occasional buyer or seller? Do you really want to have to trek to London or New York every time you want to buy or sell? And as an out-of-towner, do you really think you’d get a good deal from the locals who spend all their time there? You’d be completely out of your depth. So you’d probably value the services of an intermediary – somebody who could go to the exchange on your behalf and get you the best deal they could. We call these people stockbrokers (or just brokers). An example for retail investors may be Charles Schwab. An example for, say, pension funds might be Deutsche Bank or Morgan Stanley.

Figure 3 Brokers act on behalf of buyers and sellers

You’ll notice that “stock exchange” has become “stock exchange(s)”: this reflects the reality that there could be multiple venues you could visit to trade a particular share. This creates opportunities for arbitrage (the price may be different at each venue) but we’ll ignore this from now on.

Now this works fine if there is lots of trade in MegaCorp shares: when my broker tries to sell, there will probably be somebody else who wants to buy. But what happens if there are no buyers just then? Does that mean the share is worthless? Clearly not. So there’s an opportunity to somebody to make a living taking a bit of risk by buying and selling shares on their own account. Whereas a broker is acting in an agency capacity, this new person would make money from their wits: buying low and selling high with their own money. We call these people market-makers – since they literally create a market in the shares in which they specialize. We call firms like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley broker-dealers because some of their subsidiaries engage in both broking and market-making in various markets.

Figure 4 Market-makers buy and sell shares on their own account, creating liquidity

Guess what: we still have problems! Remember: I’ve asked my broker to sell my shares for me but imagine they succeed. Then what? We now have the tricky problem of settlement. Remember: we’re still in the days of paper-based certificates. So my broker has just sold my MegaCorp shares. Well… the buyer is going to want the certificate pretty soon. And I would quite like the cash.

Now… I could just trust my broker. I could leave the paper certificate in their hands and ask them to take receipt of the cash when the buyer’s broker hands over their cash. But that means placing a lot of trust in that individual. And remember: I chose the broker because they could navigate the rough and tumble of the stock exchange, not because I trusted their book-keeping skills!

Worse, what happens if MegaCorp issues a dividend while the share certificate is in the hands of the broker? Do they really have the ability or inclination to collect the divident, allocate it to my account and report to me about this in a timely manner? Perhaps, but probably not.

But we still have the need for somebody to keep the certificate safe and to be on hand to give it to the purchaser if a sale takes place. It’s just that the skills needed by this person are completely different to those needed by the broker. The broker needs to be able to negotiate the best price for me. But the person who looks after my certificate needs to be good with accounts, book-keeping, reporting and security. After all, I’m trusting them with the safekeeping of my share certificate: it’s in their custody. So we call these people custodians. Examples include State Street and Northern Trust, as well as divisions of Citi and HSBC, etc.

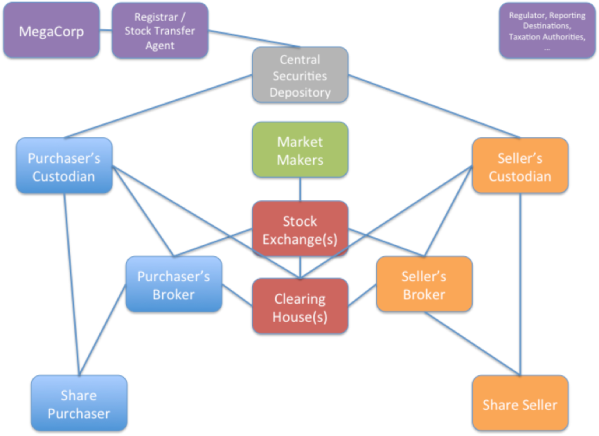

Figure 5 Custodians are responsible for the safekeeping of shares

So now, when my broker finds a willing buyer at the exchange, they can tell my custodian to expect to receive cash from the buyer’s custodian and to send the certificate to the buyer’s custodian when this happens.

And while the share certificate is sitting at the custodian, they can deal with all the tedious things that can happen to a share during its life: dividends, stock-splits, voting, … It’s as if the shares need regular attention, like an old car that needs constant servicing: so we call this business the business of securities servicing. The picture above shows a line from the buyer/seller to their custodians, because the custodian is working on their behalf. However, retail investors will probably not be aware of this relationship as their brokerage will manage the relationship on their behalf.

So… what have we achieved? I can lodge my share certificate with a custodian, instruct my broker to sell the shares on my behalf by finding a willing buyer at a stock exchange and wait for the cash to arrive. We’re done!

Erm… not so fast. There are still several problems. The first becomes obvious when you think about how the picture I’ve described would work in practice. You have loads of brokers shouting at each other, making trades all the time. It would be completely chaotic yet, somehow, we need to get to a point where the buying and selling brokers agree completely on the details of the trade they just did and have communicated matching settlement instructions perfectly to the two custodians so they can settle the trade. That’s not going to be easy.

In reality, there’s quite some work that must be done post-trade to get it to the point where it can be settled (matching, maybe netting, agreement of settlement details, agreeing on time and place of settlement, etc, etc). We call this process clearing. (I wrote previously about a real-life example of spontaneous clearing at the world’s first-ever open-outcry Bitcoin exchange.)

And there’s a second, more subtle, problem: how does my broker know that the person they’re selling to is good for the cash? And how does the buyer know that my broker can lay their hands on the shares? In the model I’ve just described, they don’t. Now, perhaps that’s not a problem: after all, smart custodians are only going to exchange shares and cash at the same time. But it’s still problematic: sure… if the buyer turns out not to have the cash, I still have my shares… but I wanted to sell them! And the price may drop before I can find a replacement buyer.

A clearing house is intended to solve both these problems. Here’s how: after a trade is matched (both sides agree on the details), the information is sent to the clearing house by the exchange. And here’s the trick: as well as orchestrating the clearing process and getting everything ready for settlement, the clearing house does something clever: it steps into the middle of the trade. In effect, it tears up the trade and creates two new ones in its place: it becomes my buyer and it becomes the seller to the buyer. In this way, I have no exposure to the buyer: if they turn out to be a fraud, it’s now the clearing house’s problem. And the ultimate seller has no exposure to me: if I turn out to be a fraud, the buyer still gets their shares (the clearing house will go into the market and buy them from somebody else if it really has to). We call this “stepping in” process novation and say that the clearing house is acting as a central counterparty if it performs this service. As an example, the London Stock Exchange uses LCH.Clearnet Ltd as its clearing house.

Of course, this amazing service comes at a price: they charge a fee and, more importantly, impose strict rules on who can be a clearing member of the exchange and how they should be run. In this way, the clearing house acts as a policeman, ensuring only people and firms with a good track record and deep resources are allowed to participate. (I’ll leave to one side whether this privileging of one group over another is a net good or bad!)

So we can update our picture again:

Figure 6 A clearing house manages the post-trade process of getting to a point where settlement can take place and often also acts as a central counterparty

We’re almost there… but there are still some loose ends. To see why, consider this from MegaCorp’s perspective. We’ve been talking about buying and selling their shares and this all happens without any involvement from them at all. That’s fine in most circumstances but it does cause problems from time to time. Specifically, what happens when the company issues a dividend or wants its shareholders to vote on something? How does it know who its shareholders are? Imagine it knew I was a shareholder. What happens after I’ve sold the shares using the system above to somebody else? How does the company get to hear about the new owner?

Enter yet another player: the registrar (UK) or share transfer agent (US). These companies work on behalf of the company and are responsible for maintaining a register of shareholders and keeping it up to date. If the company pays a dividend, these companies are responsible for distributing it. They rely on one of the participants in the process to tell them about share transfer. An example of a registrar in the UK would be Equiniti.

Figure 7 A registrar (or stock transfer agent) keeps track of who owns a company’s shares on behalf of the company

Now, I assumed up front that we were using paper certificates. And it’s amazing how far you can go in the description without needing to bring IT into the narrative at all. But, clearly, paper certificates are a complete pain. They can get lost, you have to move them around, you have to reissue them if the company does a stock split, etc. It would clearly be easier if they were electronic.

For any given custodian, it’s not a problem: they can just set up an IT book-keeping system to keep track of the share certificates under their safekeeping. And this can work well: imagine if the seller of a share uses the same custodian as the buyer: if the custodian is electronic, no paper needs to move at all! The custodian can just update its electronic records to reflect the new owner. But it doesn’t work if the buyer and seller use different custodians: you’d still need to move paper between them in this case.

So this raises an interesting possibility: what if we had a “custodian to the custodians”? If the custodians could deposit their paper certificates with a trusted third party, then they could transfer shares between each other simply by asking this “custodian to the custodians” to update its electronic records and we’d never need to move paper again!

And that’s what we have. We call these organisations central securities depositories. In the early days, they were just that: a depository where the share certificates were placed in exchange for an equivalent entry on the electronic register. The shares were, in effect, immobilized at the CSD. Over time, people gained trust in the system and agreed that there really wasn’t any need for paper certificates at all… so we moved from immobilization to dematerialization. The UK’s CSD is Euroclear (CREST).

This completes our picture (and notice how it is the CSD who informs the registrar when shares change hands… left as an exercise to a reader is thinking through what happens if shares change hands within the same custodian and what it means for the granularity of the data held by registrars):

Figure 8 A CSD acts as the “custodian to the custodians”

This picture also introduces regulators, governments and taxation authorities, for completeness. However, I don’t discuss them here. I also don’t discuss what happens if you’re trading shares cross-border.

So now we have the full story: if I want to sell some MegaCorp shares, here’s what happens:

- My shares start off in the account of my broker, who uses a custodian for safekeeping

- The broker executes a sale at an exchange

- The clearing house establishes everybody’s respective liabilities, steps in as central counterparty and orchestrates the settlement process

- The buyer’s and seller’s custodians exchange shares for cash (“Delivery versus Payment”), utilizing the CSD if shares need to move between custodians as a result. Assuming so, the company’s registrar is informed.

- Somebody probably has to pay some tax J

You’ll notice many parallels with the global payments system: lots of intermediaries and lots of specialists – all of them there for a reason but imposing costs nonetheless.

Now, I said I would use this narrative to discuss what it could mean for Bitcoin “colored coins”. I think there are two key concepts that can help us think through workable models: risk and the meaning of settlement.

Risk

Consider the picture above: what risks are you exposed to as an investor? Ideally, if you buy shares in MegaCorp, the only risks you want to be exposed to are those associated with MegaCorp itself, realized through changes in share price or dividend payments. So, the ideal state is when you just face this market risk. And that’s broadly what the system above delivers: by depositing your shares in a custodian bank, which should keep them in a segregated account at the CSD, you’re protected even if the custodian goes bust: your shares are not considered part of the custodian bank’s assets. So the only risk you’re exposed to beyond the market risk (which you want) is operational risk that the custodian makes a mistake. (I’ll ignore cash here but note that it’s typically not protected in the same way)

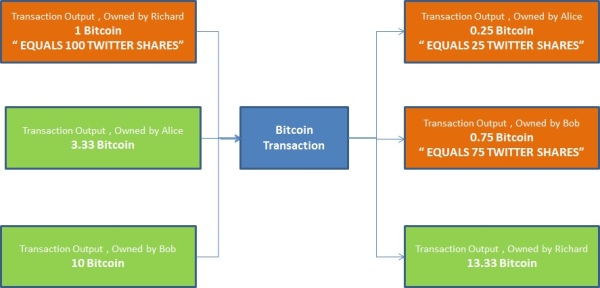

Now, when we look at “colored coin” share representation schemes, we see there is the notion of a colored coin “issuer”: somebody who asserts that a given set of coins represents a particular number of shares in a particular company. So now we have a big question: who is this somebody? This matters because if the “somebody” reneges on their promise or goes bust, you’ve lost your shares.

Now, if a colored coin scheme were “grafted on” to today’s system, it could work quite well if done right. Imagine a firm wanted to offer colored coins representing 100 MegaCorp shares. They could open a custody account, fund it with 100 MegaCorp shares as “backing” and we’d be done: such firms could perhaps compete on the completeness of their transparency. However, owners of colored MegaCorp coins would have counterparty exposure to this firm, which means the risk profile would be different (worse?) than if they simply owned coins in a regular custody account.

Interestingly, you can’t overcome the problem entirely by having a custodian bank be the issuer because it’s not obvious to me that a coloured MegaCorp coin issued by a custodian bank is the same as a segregated share for the purposes of bankruptcy protection: you’d presumably also need a legal opinion – and I am not a lawyer!

Bottom line: there is work to do for those developing these schemes.

However, there is one intriguing possibility with this approach: think through what happens if MegaCorp themselves were to issue colored coins representing their shares. Any analysis of counterparty risk becomes moot: if MegaCorp went bust, you’d lose your money regardless of how your shares were held! Perhaps this is the future? (Note also that I’m not discussing here precisely why anybody would want to issue – or buy – coloured coins! I’ll leave that to others)

Do you actually want settlement?

However, there’s another way of looking at this: you don’t have to own a share to enjoy the benefits of ownership. Contracts for Difference (or, more generally, Equity Swaps) allow you to enjoy the losses or gains from owning a stock without actually owning it. They are, instead, contracts, with a counterparty, in which the counterparty pays (or receives) cash that matches the gain or loss in the share price (and payment of dividends). Now, the counterparty often hedges their risk by buying the shares – but that becomes their problem, not yours. So this gives you all the benefits of owning the stock without having to go through the pain of actually taking delivery. It also has tax advantages in some jurisdictions.

The downside is that you take on counterparty risk to the party issuing the CFD: if they go bust while you’re in the money, you’re out of luck. But we’ve already established that there could well be quite considerable counterparty risk with colored coins in any case. So perhaps this is the right model. I don’t yet have a view on which will prevail but hopefully laying out how today’s system is constructed will help others think this through more clearly.

I’ll end with one final observation: the issuance is the easy part.. but somebody still has to do the servicing. But notice how this is much easier if you use a technology such as the Block Chain: there’s no need for the arbitrary distinctions between custodian, CSD and registrar: the issuer can see immediately which addresses own their coins and to whom they should send messages or dividends. Similarly, the peer-to-peer nature of Bitcoin means the hierarchy of custodians and CSDs could possibly be collapsed.

I know many people think blockchain technology could be hugely disruptive for the world’s banks but I look at it another way: I believe there are huge opportunities for those financial firms that really take the time to study this space.

[Final comment: a reminder to readers that this is my personal blog and the opinions are mine alone… I don’t speak on behalf of my employer]

[Update – 2014-01-07 – One question I failed to address above is precisely why anybody would want to settle share trades using a coloured coin scheme! I think there are two possible answers:

1) if settlement can be effected over the blockchain, the cost potentially reduces to the fee of the Bitcoin transaction in simple cases

2) if opens up the potential for custodians, CSDs and registrars/stock transfer agents to innovate their business models in a new way: do they still need to be separate entities, for example? Further, would ‘regular’ companies see value in becoming their own issuers, etc?

However, I’m not convinced this approach does anything to reduce risk – the challenge would be how to build a system with risk as good as what we have today. ]