Twitter went mad last week because somebody had transferred almost $150m in a single Bitcoin transaction. This tweet was typical:

There was much comment about how expensive or difficult this would have been in the regular banking system – and this could well be true. But it also highlighted another point: in my expecience, almost nobody actually understands how payment systems work. That is: if you “wire” funds to a supplier or “make a payment” to a friend, how does the money get from your account to theirs?

In this article, I hope to change this situation by giving a very simple, but hopefully not oversimplified, survey of the landscape.

First, let’s establish some common ground

Perhaps the most important thing we need to realise about bank deposits is that they are liabilities. When you pay money into a bank, you don’t really have a deposit. There isn’t a pot of money sitting somewhere with your name on it. Instead, you have lent that money to the bank. They owe it to you. It becomes one of their liabilities. That’s why we say our accounts are in credit: we have extended credit to the bank. Similarly, if you are overdrawn and owe money to the bank, that becomes your liability and their asset. To understand what is going on when money moves around, it’s important to realise that every account balance can be seen in these two ways.

Paying somebody with an account at the same bank

Let’s start with the easy example. Imagine you’re Alice and you bank with, say, Barclays. You owe £10 to a friend, Bob, who also uses Barclays. Paying Bob is easy: you tell the bank what you want to do, they debit the funds from your account and credit £10 to your friend’s account. It’s all done electronically on Barclays’ core banking system and it’s all rather simple: no money enters or leaves the bank; it’s just an update to their accounting system. They owe you £10 less and owe Bob £10 more. It all balances out and it’s all done inside the bank: we can say that the transaction is “settled” on the books of your bank. We can represent this graphically below: the only parties involved are you, Bob and Barclays. (The same analysis, of course, works if you’re a Euro customer of Deutsche Bank or a Dollar customer of Citi, etc)

But what happens if you need to pay somebody at a different bank?

This is where it get more interesting. Imagine you need to pay Charlie, who banks with HSBC. Now we have a problem: it’s easy for Barclays to reduce your balance by £10 but how do they persuade HSBC to increase Charlie’s balance by £10? Why would HSBC be interested in agreeing to owe Charlie more money than they did before? They’re not a charity! The answer, of course, is that if we want HSBC to owe Charlie a little more, they need to owe somebody else a little less.

Who should this “somebody else” be? It can’t be Alice: Alice doesn’t have a relationship with HSBC, remember. By a process of elimination, the only other party around is Barclays. And here is the first “a ha” moment… what if HSBC held a bank account with Barclays and Barclays held a bank account with HSBC? They could hold balances with each other and adjust them to make everything work out…

Here’s what you could do:

- Barclays could reduce Alice’s balance by £10

- Barclays could then add £10 to the account HSBC holds with Barclays

- Barclays could then send a message to HSBC telling them that they had increased their balance by £10 and would like them, in turn, to increase Charlie’s balance by £10

- HSBC would receive the message and, safe in the knowledge they had an extra £10 on deposit with Barclays, could increase Charlie’s balance.

It all balances out for Alice and Charlie… Alice has £10 less and Charlie has £10 more.

And it all balances out for Barclays and HSBC. Previously, Barclays owed £10 to Alice, now it owes £10 to HSBC. Previously, HSBC was flat, now it owes £10 to Charlie and is owed £10 by Barclays.

This model of payment processing (and its more complicated forms) is known as correspondent banking. Graphically, it might look like the diagram below. This builds on the previous diagram and adds the second commercial bank and highlights that the existence of a correspondent banking arrangement allows them to facilitate payments between their respective customers.

This works pretty well, but it has some problems:

- Most obviously, it only works if the two banks have a direct relationship with each other. If they don’t, you either can’t make the payment or need to route it through a third (or fourth!) bank until you can complete a path from A to B. This clearly drives up cost and complexity. (Some commentators restrict the use of the term “correspondent banking” to this scenario or scenarios that involve difference currencies but I think it helpful to use the term even for the simpler case)

- More worryingly, it is also risky. Look at the situation from HSBC’s perspective. As a result of this payment, their exposure to Barclays has just increased. In our example, it is only by £10. But imagine it was £150m and the correspondent wasn’t Barclays but was a smaller, perhaps riskier outfit: HSBC would have a big problem on its hands if that bank went bust. One way round this is to alter the model slightly: rather than Barclays crediting HSBC’s account, Barclays could ask HSBC to debit the account it maintains for Barclays. That way, large inter-bank balances might not build up. However, there are other issues with that approach and, either way, the interconnectedness inherent in this model is a very real problem.

We’ll work through some of these issues in the following sections.

[Note: this isn’t *actually* what happens today because the systems below are used instead but I think it’s helpful to set up the story this way so we can build up an intuition for what’s going on]

Hang on… why are you making this so complicated? Can’t you just say “SWIFT” and be done with it?

It is common when discussing payment systems to have somebody wave their hands, shout “SWIFT” and believe they’ve settled the debate. To me, this just highlights that they probably don’t know what they’re talking about 🙂

The SWIFT network exists to allow banks securely to exchange electronic messages with each other. One of the message types supported by the SWIFT network is MT103. The MT103 message enables one bank to instruct another bank to credit the account of one of their customers, debiting the account held by the sending institution with the receiving bank to balance everything out. You could imagine an MT103 being used to implement the scenario I discussed in the previous section.

So, the effect of a SWIFT MT103 is to “send” money between the two banks but it’s critically important to realise what is going on under the covers: the SWIFT message is merely the instruction: the movement of funds is done by debiting and crediting several accounts at each institution and relies on banks maintaining accounts with each other (either directly or through intermediary banks). Simply waving one’s hands and shouting “SWIFT” serves to mask this complexity and so impedes understanding.

OK… I get it. But what about ACH and EURO1 and Faster Payments and BACS and CHAPS and FedWire and Target2 and and and????

Slow down….. Let’s recap first.

We’ve shown that transferring money between two account holders at the same bank is trivial.

We’ve also shown how you can send money between account holders of different banks through a really clever trick: arrange for the banks to hold accounts with each other.

We’ve also discussed how electronic messaging networks like SWIFT can be used to manage the flow of information between banks to make sure these transfers occur quickly, reliably and at modest cost.

But we still have further to go… because there are some big problems: counterparty risk, liquidity and cost.

The two we’ll tackle first are liquidity and cost

We need to address the liquidity and cost problem

First, we need to acknowledge that SWIFT is not cheap. If Barclays had to send a SWIFT message to HSBC every time you wanted to pay £10 to Charlie, you would soon notice some hefty charges on your statement. But, worse, there’s a much bigger problem: liquidity.

Think about how much money Barclays would need to have tied up at all its correspondent banks every day if the system I outlined above were used in practice. They would need to maintain sizeable balances at all the other banks just in case one of their customers wanted to send money to a recipient at HSBC or Lloyds or Co-op or wherever. This is cash that could be invested or lent or otherwise put to work.

But there’s a really nice insight we can make: on balance, it’s probably just as likely that a Barclays customer will be sending money to an HSBC customer as it is that an HSBC customer will be sending money to a Barclays customer on any given day.

So what if we kept track of all the various payments during the day and only settled the balance?

If you adopted this approach, each bank could get away with holding a whole lot less cash on deposit at all its correspondents and they could put their money to work more effectively, driving down their costs and (hopefully) passing on some of it to you. This thought process motivated the creation of deferred net settlement systems. In the UK, BACS is such a system and equivalents exist all over the world. In these systems, messages are not exchanged over SWIFT. Instead, messages (or files) are sent to a central “clearing” system (such as BACS), which keeps track of all the payments, and then, on some schedule, calculates the net amount owed by each bank to each other. They then settle amongst themselves (perhaps by transferring money to/from the accounts they hold with each other) or by using the RTGS system described below.

This dramatically cuts down on cost and liquidity demands and adds an extra box to our picture:

It’s worth noting that we can also describe the credit card schemes and even PayPal as Deferred Net Settlement systems: they are all characterised by a process of internal aggregation of transactions, with only the net amounts being settled between the major banks.

But this approach also introduces a potentially worse problem: you have lost settlement finality. You might issue your payment instruction in the morning but the receiving bank doesn’t receive the (net) funds until later. The receiving bank therefore has to wait until they receive the (net) settlement, just in case the sending bank goes bust in the interim: it would be imprudent to release funds to the receiving customer before then. This introduces a delay.

The alternative would be to take the risk but reverse the transaction in the event of a problem – but then the settlement couldn’t in any way be considered “final” and so the recipient couldn’t rely on the funds until later in any case.

Can we achieve both Settlement Finality and Zero Counterparty Risk?

This is where the final piece of the jigsaw fits in. None of the approaches we’ve outlined so far are really acceptable for situations when you need to be absolutely sure the payment will be made quickly and can’t be reversed, even if the sending bank subsequently goes bust. You really, really need this assurance, for example, if you’re going to build a securities settlement system: nobody is going to release $150m of bonds or shares if there’s a chance the $150m won’t settle or could be reversed!

What is needed is a system like the first one we outlined (Alice pays Bob at the same bank) – because it’s really quick – but which works when more than one bank is involved. The multilateral bank-bank system outlined above sort-of works but gets really tricky when the amounts involved get big and when there’s the possibility that one or other of them could go bust.

If only the banks could all hold accounts with a bank that cannot itself go bust… some sort of bank that sat in the middle of the system. We could give it a name. We could call it a central bank!

And this thought process motivates the idea of a Real-Time Gross Settlement system.

If the major banks in a country all hold accounts with the central bank then they can move money between themselves simply by instructing the central bank to debit one account and credit the other. And that’s what CHAPS, FedWire and Target 2 exist to do, for the Pound, Dollar and Euro, respectively. They are systems that allow real-time movements of funds between accounts held by banks at their respective central bank.

- Real Time – happens instantly.

- Gross – no netting (otherwise it couldn’t be instant)

- Settlement – with finality; no reversals

This completes our picture:

I thought this article had something to do with Bitcoin?

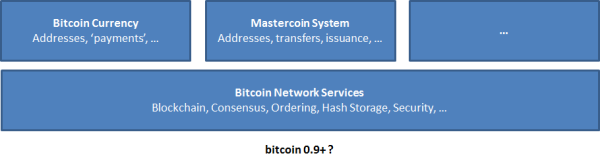

Well done for getting this far. Now we have a question: can we place Bitcoin on this model?

My take is that the Bitcoin network most closely resembles a Real-Time Gross Settlement system. There is no netting, there are (clearly) no correspondent banking relationships and we have settlement, gross, with finality.

But the interesting thing about today’s “traditional” financial landscape is that most retail transactions are not performed over the RTGS. For example, person-to-person electronic payments in the UK go over the Faster Payments system, which settles net several times per day, not instantly. Why is this? I would argue it is primarily because FPS is (almost) free, whereas CHAPS payments cost about £25. Most consumers probably would use an RTGS if it were just as convenient and just as cheap.

So the unanswered question in my mind is: will the Bitcoin payment network end up resembling a traditional RTGS, only handling high-value transfers? Or will advances in the core network (block size limits, micropayment channels, etc) occur quickly enough to keep up with increasing transaction volumes in order to allow it to remain an affordable system both for large- and low-value payments?

My take is that the jury is still out: I am convinced that Bitcoin will change the world but I’m altogether less convinced that we’ll end up in a world where every Bitcoin transaction is “cleared” over the Blockchain.

[Updated several times on 25 November 2013 to correct minor errors and to add the link to my Finextra video at the end]